Extracting a Biometric Sample definition

Extracting a biometric sample is the process that follows capturing, where the raw biometric data like a fingerprint image, face photo, iris scan, or palm scan is processed by specialized algorithms to produce a set of distinguishing features, which is commonly called a biometric template. In simpler terms, once a biometric image or recording is taken, a feature extraction program analyzes it to pull out the unique patterns, such as fingerprint minutiae points, facial characteristics, iris textures, or palm line patterns, and converts those into a mathematical representation suitable for computer comparison.

This step is essential in biometric systems because the raw sample is typically too bulky and inconsistent for direct matching, whereas the extracted template is a compact, standardized digital summary of the person’s unique traits.

Why Extracting a Biometric Sample Matters

Extraction is a critical middle step between collecting a biometric and comparing it against others. The quality and accuracy of the extraction step directly influence the success of biometric recognition. If the captured sample is poor due to a blurry fingerprint, dimly lit face, or off-angle iris, the feature extractor may fail to generate a useful template at all, or produce a template that is missing important details. In those cases, the system might log a failure to process error (meaning it couldn’t extract features) or, worse, create a subpar template that leads to false non-matches or false matches later during comparison.

On the other hand, a robust extraction algorithm can sometimes enhance or normalize a decent sample to make the most of it. Modern extraction techniques often include preprocessing steps like filtering out background noise, enhancing contrast, or aligning the biometric data to improve feature detection. A good extractor will yield a template that captures all the salient information available in the sample while discarding irrelevant data. This maximizes matching accuracy and speed, since templates are designed to be lightweight and focused on discriminatory features.

It’s also important for consistency and interoperability. If everyone’s biometric templates are extracted using the same standards and criteria, then comparisons become more reliable across devices and systems. In fact, international standards exist to guide biometric feature extraction and template formats. Independent evaluations like NIST’s interoperability tests (e.g., MINEX III for fingerprint templates) specifically check that an extractor from one provider can work with a matcher from another.

Mapping the Extraction Pipeline

Once a biometric sample is captured and ready, the system typically goes through a series of steps to extract and prepare the biometric template:

- Preprocessing: The raw data is first preprocessed to improve feature detection. This can include noise reduction and normalization. The goal of preprocessing is to present the feature extractor with a standardized, high-quality input.

- Feature Extraction Algorithm: Next comes the core extraction. Here, software algorithms analyze the preprocessed sample to detect distinctive attributes of the biometric. Essentially, the algorithm converts the image into a mathematical pattern. At this stage, the raw image is effectively distilled into a set of numbers or binary data that captures its unique identity.

- Quality Check & Decision: Many systems include an intermediate quality check on the extracted features. The system can then decide: proceed with this template or reject it and ask for a new sample. This is analogous to the quality checks done right after capture, but here the focus is on whether the template itself has enough data.

- Template Creation & Storage: The final step is formatting and storing the extracted data as a biometric template. The features extracted (minutiae coordinates, feature vectors, etc.) are packaged into a standardized data structure – often according to a format specification or proprietary schema. This template is much smaller than the original image (often just a few hundred bytes). At this point, the template can be encrypted or signed for security before storage.

These steps happen quickly, often in a fraction of a second on modern devices, but each is crucial. Together, they ensure that by the time we have a template, it’s a reliable and optimized representation of the person’s biometric trait.

Biometric Modalities and How Extraction Differs

The fundamental goal of extraction is the same across all biometric modalities, which is to get a unique digital signature of the person, but the techniques and data extracted differ by modality. Here’s how feature extraction works for four major biometric types:

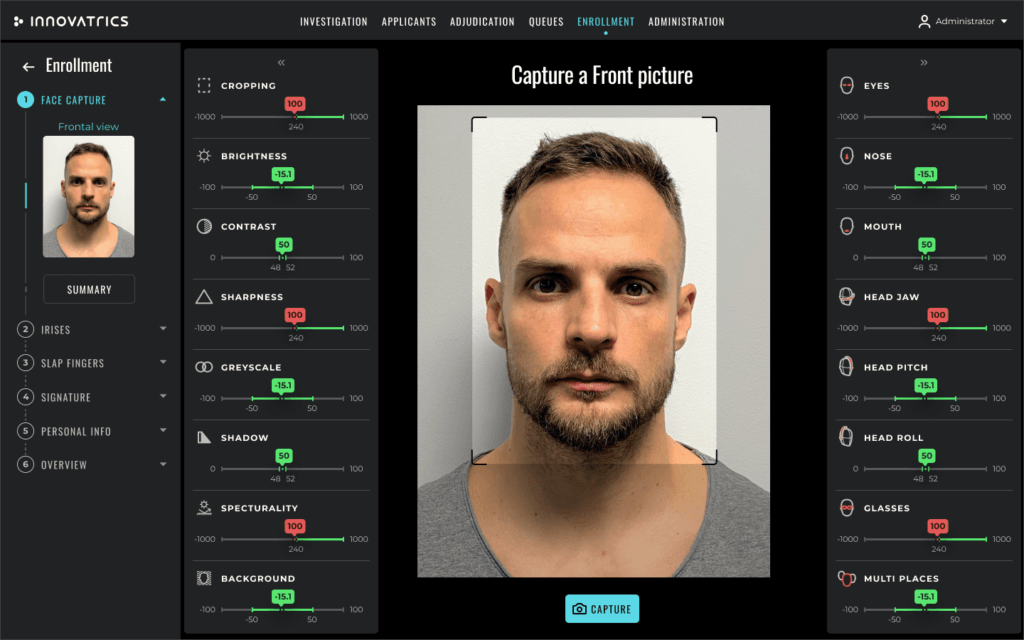

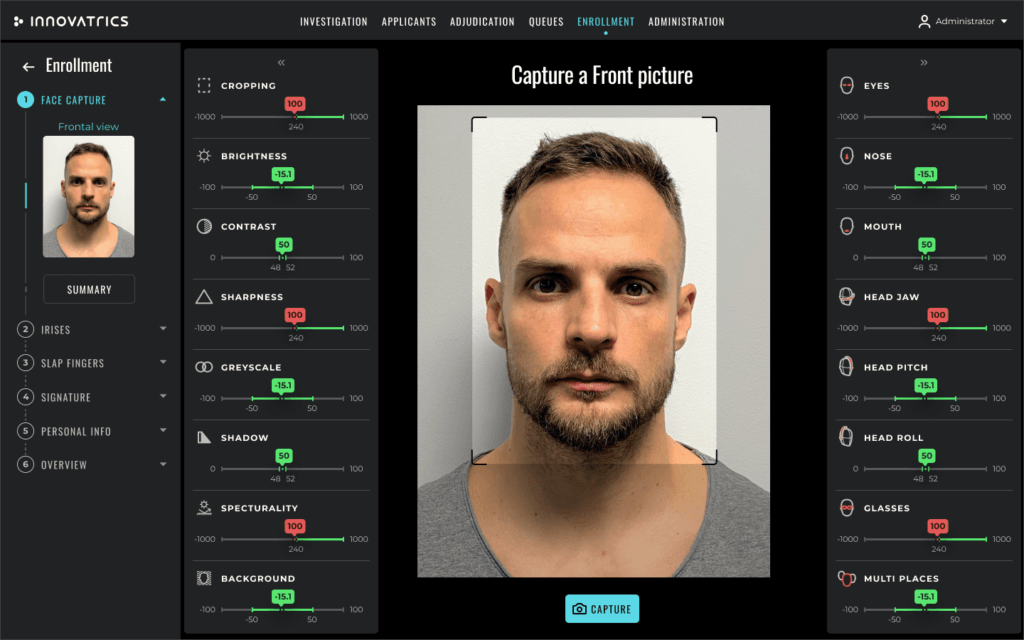

Face Extraction

For faces, extraction typically relies on sophisticated machine learning. Modern face recognition systems use deep neural networks to process a face image and output a numerical vector that represents that face. During training, the neural network learned to emphasize features of the face that distinguish individuals (like the relative shapes of facial features, bone structure, etc.) while ignoring superficial differences (like lighting or background). Innovatrics and many other vendors use neural networks trained on millions of face images to extract these features. The resulting face template is usually a compact feature vector: you can think of it as a point in a high-dimensional space, where each person’s face corresponds to a unique point in that space.

The face extraction process usually includes detecting the face in the image and aligning it (so that the eyes, nose, and mouth are in expected positions). The neural network then produces the feature vector. Unlike older methods that might have measured distances between specific facial landmarks or hand-crafted features, today’s deep learning approach lets the network determine the most salient features automatically.

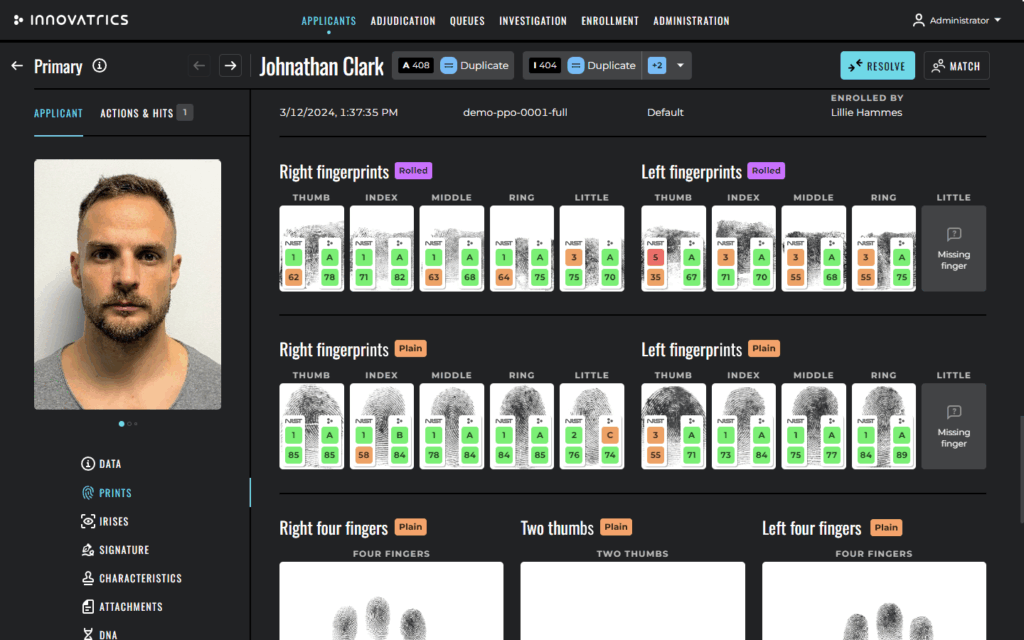

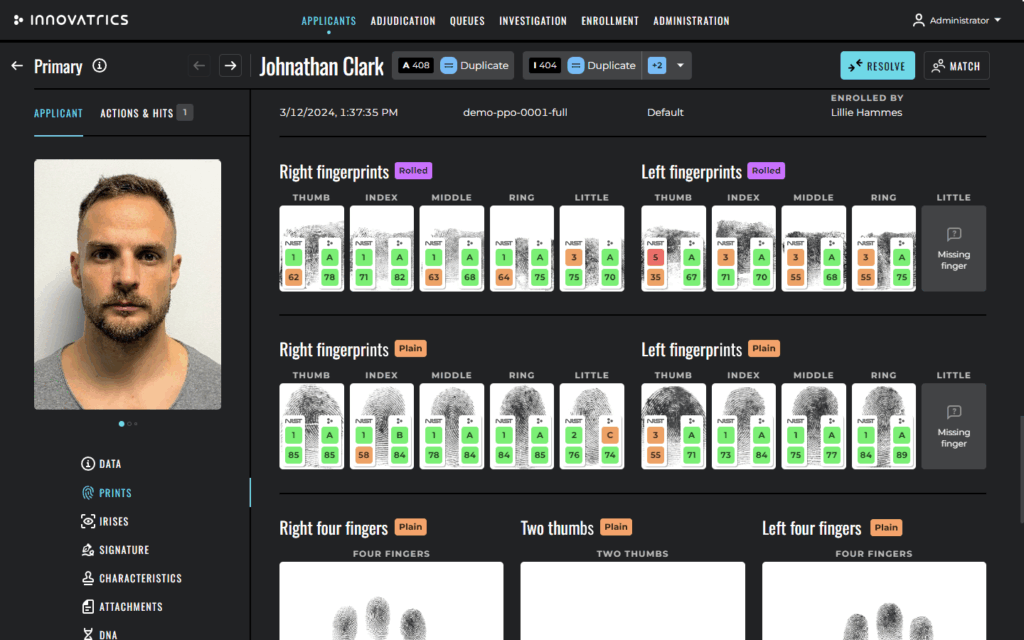

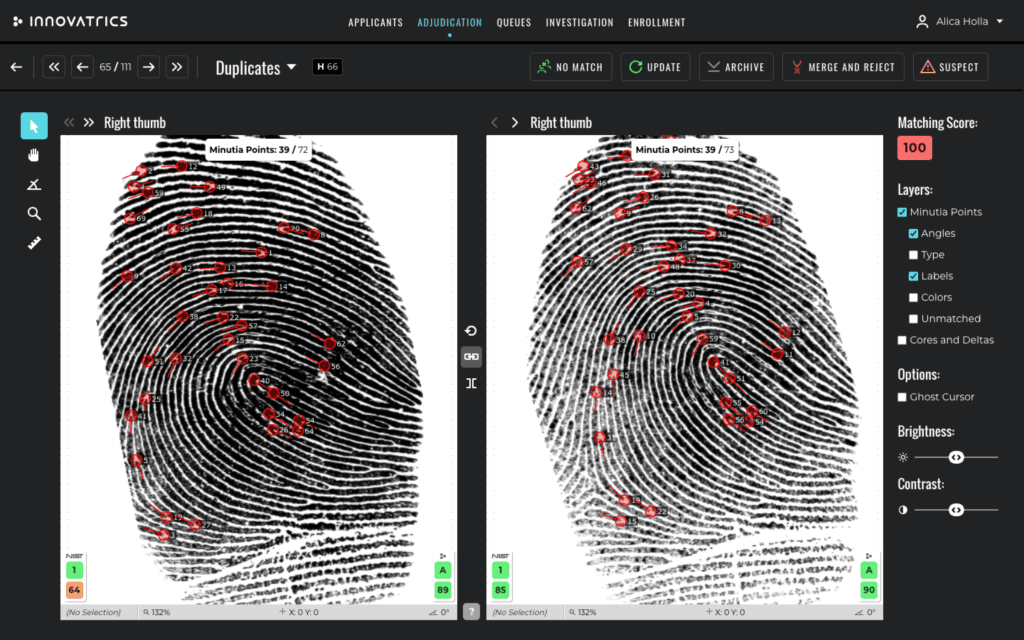

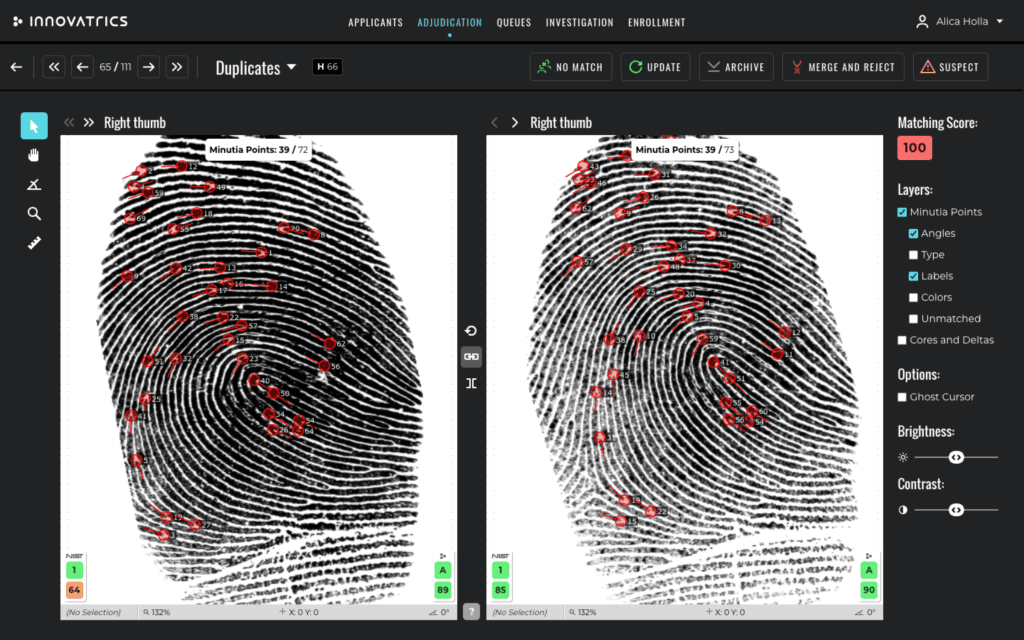

Fingerprint Extraction

Fingerprint extraction is a more mature and standardized process, rooted in decades of forensic science. When a fingerprint image is captured, the extractor software analyzes the pattern of ridges and furrows. The primary features extracted are called minutiae – specifically, ridge endings (where a ridge line terminates) and ridge bifurcations (where a ridge splits into two). Each minutia can be described by its coordinates on the fingerprint and the angle or direction of the ridge at that point. These minutiae points form the basis of the fingerprint template.

A template can be stored as a compact file listing each minutia’s X/Y position, angle, and type. This allows different organizations or systems to share fingerprint templates if needed. Extractors that comply with these standards can be evaluated independently – the U.S. NIST’s MINEX tests evaluate fingerprint extractors and matchers to ensure, for example, that a minutiae template created by one algorithm can be accurately matched by another. High-performing fingerprint extraction algorithms today not only find minutiae accurately but also filter out false minutiae and might even utilize machine learning to enhance or validate the features.

Iris Extraction

Iris recognition is often cited as one of the most accurate biometric methods, and that’s largely due to the richness of features that can be extracted from the human iris. The iris is the colored ring around the pupil, with intricate patterns of crypts, furrows, rings, and freckles that are unique to each eye. To extract an iris’s features, the captured eye image is first preprocessed: the system locates the iris region (between pupil and sclera), and typically unwraps it to a normalized rectangular form (imagine “flattening” the donut shape of the iris into a band). This compensates for eye rotation and pupil dilation. Then, a filter (classically, Gabor wavelets in multiple orientations and scales) is applied to this normalized iris texture to quantify the patterns. An emerging trend is using neural networks for iris feature extraction, similar to faces.

Innovatrics notes that their iris algorithm is also based on neural networks trained on diverse iris images.

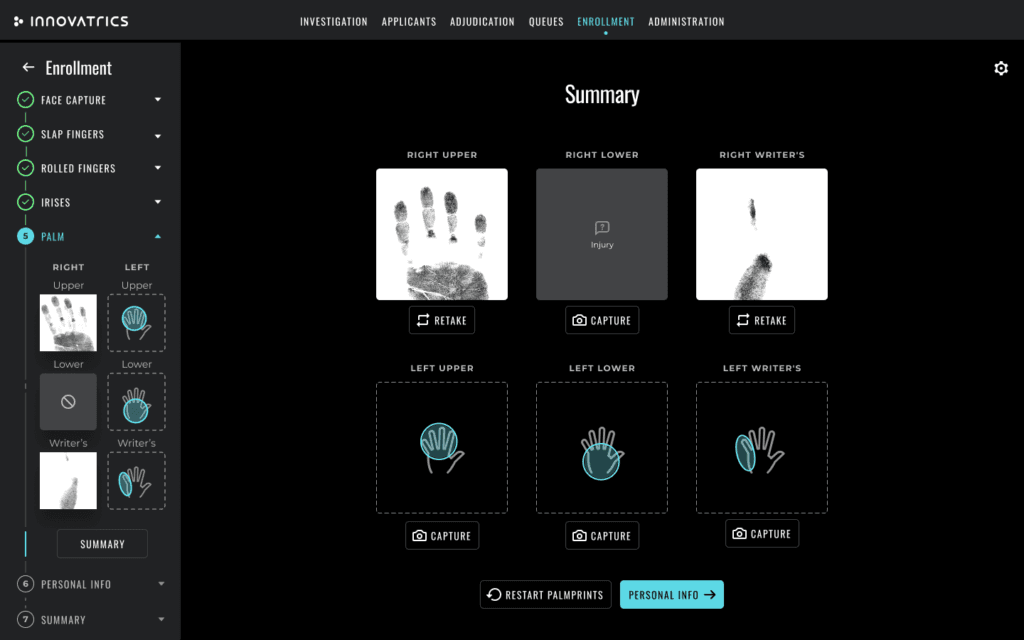

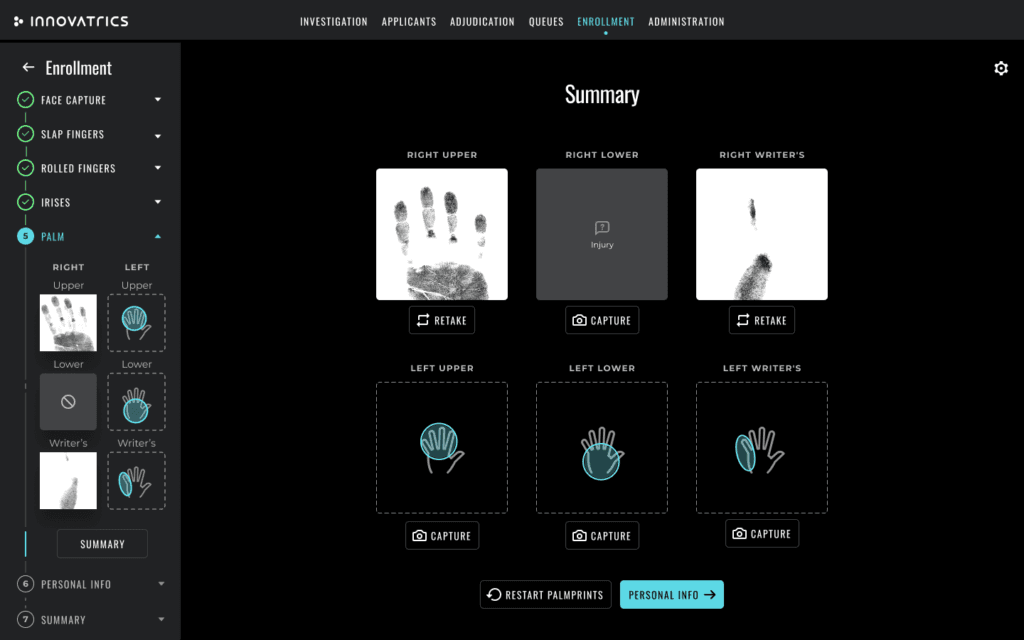

Palm Extraction

Palm biometrics can refer to either palm print recognition or palm vein recognition, or a combination of both. Innovatrics focuses on contactless palm print recognition, which analyzes the surface of the palm (the skin ridges and lines, much like a large fingerprint) using just a standard camera. Extracting features from a palm print is quite similar to fingerprint extraction, just on a bigger scale. A palm image contains many features: the overall line patterns, friction ridges that cover the palm (which have minutiae points just like fingerprints), and sometimes even pores or texture. A palm print extractor will often detect minutiae points across the whole palm, possibly hundreds of them, since a palm covers a larger area than a single finger. It may also record feature lines or creases if useful. The resulting palm template might be an extended set of minutiae or a mixture of minutiae and other keypoints.

Palm extractors, especially contactless ones, put emphasis on overcoming variable presentation – different people might hold their hands at slightly different angles or distances. So the preprocessing might involve correcting perspective or scaling before feature detection. Once features are extracted, the palm template is again just a digital summary of those features. Matching two palm templates involves comparing large sets of points or patterns. Like fingerprints, palm recognition has been standardized to some extent and tested – for instance, NIST’s evaluations have included palmprint matching, and algorithms have shown accuracy on palms comparable to fingerprints.

What’s the Difference Between Enrollment and Verification Extraction?

Do we extract features differently when enrolling someone versus when simply verifying their identity? In terms of algorithm, the feature extraction process is usually the same – the software will generate the same template from the same fingerprint, whether it’s during enrollment or a login attempt. However, the context and standards around extraction can differ between these scenarios:

Enrollment Extraction

- Enrollment is the first time a person’s biometric is captured for the system, so there’s an emphasis on getting it right. Often multiple samples are taken (e.g., three fingerprint scans or several face shots) to ensure a high-quality template can be extracted. The extractor might be run on each sample, and the best template (or a composite) is stored. Because the enrollment template will serve as the reference for all future matches, the system may apply stricter quality thresholds here. In an enrollment setting like a government ID registration, operators are trained to keep capturing until the extraction module produces an acceptable template. Standards like ISO/IEC or ICAO guidelines for passports explicitly mandate certain quality metrics at enrollment, precisely to ensure the extraction creates excellent templates that will work for years to come.

Verification (or Identification) Extraction

- In verification, a person’s live sample is captured and features are extracted to compare against their enrolled reference template (1:1 check), or in identification, to search in a database (1:N). This happens routinely (think unlocking your phone with a face or finger, or passing through passport control). In these cases, there’s usually only one quick attempt to capture and extract features, for the sake of speed and user convenience. The extraction algorithm is the same, but the system might tolerate a bit more variability. For example, the template derived during verification might not be quite as perfect as the enrollment one, and that’s expected, since day-to-day captures can be a bit off. The matching process often accounts for this by using thresholds that allow some variance. If a verification attempt fails because the extracted template didn’t match (maybe due to poor extraction from a smudged finger), the user is typically allowed to try again. Generally, verification extraction is quick and assumes the enrollment template it’s being compared to is of high quality.