Synthetic Identity Fraud definition

Synthetic identity fraud occurs when criminals create fictitious identities by combining real and fabricated personal information, such as name, social security number, and address to create fraudulent accounts and obtain credit. Unlike traditional identity theft, where fraudsters steal a complete existing identity, synthetic identity fraud involves manufacturing entirely new personas that appear legitimate to verification systems.

How Does Synthetic Identity Fraud Work?

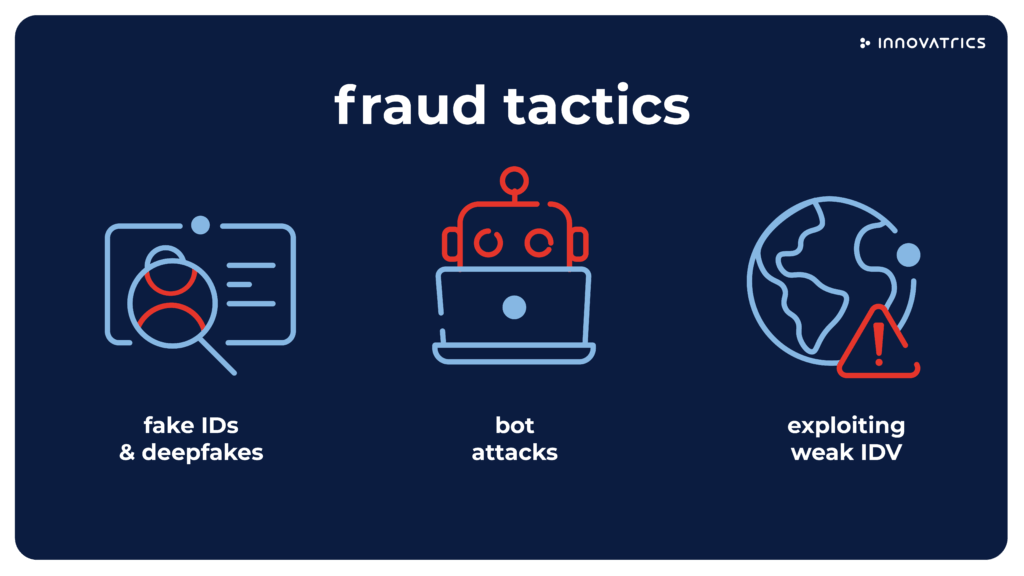

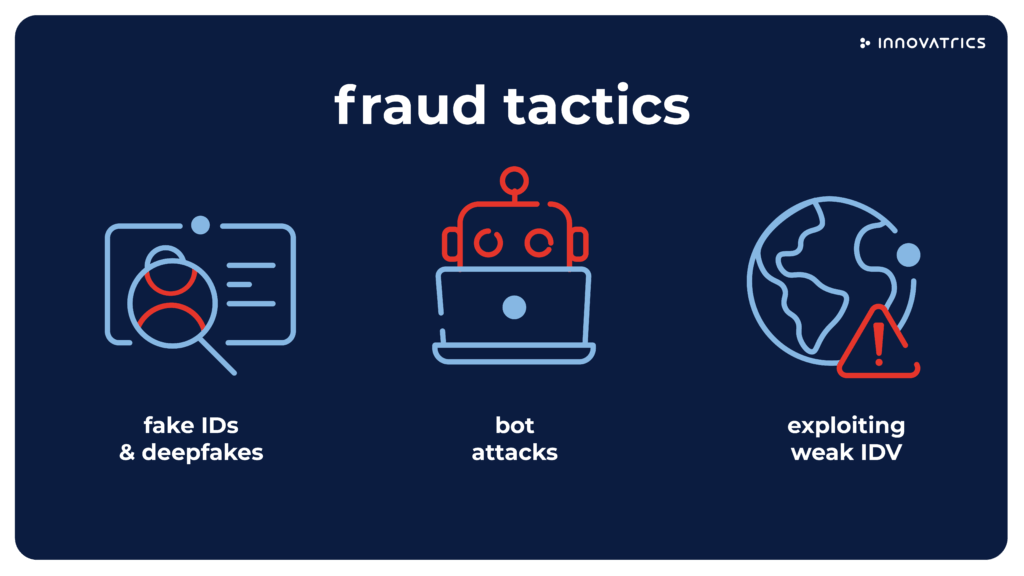

Synthetic identity fraud operates through a methodical process that exploits vulnerabilities in identity verification systems:

Collecting Personal Data

Fraudsters often combine stolen personal information, such as Social Security numbers, especially those belonging to children or the deceased, which are less monitored with fabricated details like false names, addresses, and dates of birth.

Credit Profile Establishment

Synthetic identity is used to apply for credit, initially resulting in rejections due to the thin or nonexistent credit file. However, these applications create a credit record that fraudsters then cultivate over months or years.

Identity Seasoning

Criminals gradually build the synthetic identity’s credibility by becoming authorized users on legitimate credit accounts, making small purchases, and maintaining positive payment histories. This “seasoning” period establishes creditworthiness and trust.

Racking Up Debt

Once the synthetic identity has accumulated substantial credit lines across multiple institutions, fraudsters maximize borrowing and disappear without repayment, leaving significant losses for financial institutions. This tactic may also be associated with broader money laundering schemes.

Types of Synthetic Identity

Fraudsters employ a variety of synthetic identity techniques to successfully carry out their fraudulent schemes:

Manipulated Synthetic Identities

This technique involves fraudsters altering one or two digits of a valid Social Security Number (SSN). The resulting number passes basic validation checks because it exploits the Social Security Administration’s numbering system, yet it does not correspond to any existing record.

Manufactured Synthetic Identities

These are completely fabricated identities with no ties to real people. Criminals create these identities by generating Social Security Numbers (SSNs) based on their knowledge of valid SSN ranges and issuance patterns.

Compiled Synthetic Identities

Fraudsters combine real information from multiple victims, such as one person’s SSN, another’s name, and a third’s address. This approach leverages stolen data while creating an identity that doesn’t fully match any single person.

Who Is Most Vulnerable to Synthetic Identity Fraud?

There is a certain population of people who are easy targets when it comes to identity theft and various forms of identity-related fraud. These individuals often possess characteristics or circumstances that make their personal information more accessible, less protected, or simply more desirable for criminals looking to perpetrate fraudulent schemes.

These vulnerable populations may include:

Minors and Children

Minors’ SSNs provide ideal targets because their credit will not be checked for years, giving fraudsters extended time to exploit the synthetic identity. The fraud often goes undetected until the victim applies for student loans or their first credit card.

The Elderly

Because they are often less technologically savvy and more trusting, the elderly are susceptible to impersonation fraud, phishing scams, and unknowingly disclosing personal information.

The Recently Deceased

Their identities may remain active in some systems for a period, which fraudsters exploit to open new accounts or file fraudulent tax returns before the death is widely reported and accounts are fully shut down.

Recent Immigrants

People new to a country’s credit system may have valid identification numbers but thin credit files, creating opportunities for synthetic identity creation.

People Who Have Experienced a Data Breach

While often a victim of circumstance, individuals whose information has been compromised in a large-scale breach are automatically targeted because their data is already circulating among criminal networks.

How Does Biometrics Help Prevent Synthetic Identity Fraud?

To effectively combat synthetic identity fraud, biometrics should be employed to achieve two key outcomes: ensuring a genuine person is linked to only one identity and identifying any attempts at repeat enrollments.

Face Verification (1:1)

This is a foundational step, specifically during the digital onboarding process. It involves a one-to-one comparison of a newly captured biometric (e.g., a selfie) against the biometric data linked to the claimed identity record (e.g., the photo on a presented ID document or an existing authoritative source). It confirms the applicant’s identity from the start, preventing impersonation and ensuring the system ties a real human to the correct identity.

Liveness Detection

Crucial for remote and digital transactions, liveness detection verifies that the biometric sample being captured is coming from a live human being currently present at the point of capture, rather than a fabricated artifact or a replay attack.

Deduplication (1:N)

This is arguably the most powerful tool against synthetic identity fraud at scale. Deduplication involves comparing the newly captured face against an entire database of existing and previous enrollments within an organization’s system (1:N). Its objective is to detect the same face enrolling as multiple “different” people. A hit in a deduplication search indicating that a single person has successfully registered or attempted to register multiple accounts under various names, dates of birth, or addresses is one of the clearest and most actionable signals of synthetic identity fraud in progress.

Ongoing Re-verification

To sustain a high level of security throughout the customer lifecycle, organizations must implement ongoing re-verification. This involves utilizing step-up biometric checks whenever a high-risk or sensitive event occurs. By requiring a fresh biometric verification at these junctures, organizations can confirm the current user is the original account holder, thereby preventing account takeover, which often precedes synthetic fraud activity.

How Can Organizations Prevent Synthetic Identity Fraud?

Preventing synthetic identity fraud requires multi-layered strategies combining technology, processes, and regulatory compliance:

- Advanced Biometric Verification: Implementing face recognition, liveness detection, and document authentication technologies ensure that account applicants are real, unique individuals. Biometric identity verification creates an immutable link between a person and their credentials that synthetic identities cannot replicate.

- Comprehensive Data Cross-Referencing: Organizations should validate identity data against multiple authoritative sources, including government databases, utility records, and employment history. Inconsistencies across datasets often reveal synthetic identities.

- Behavioral Analytics: Machine learning models that analyze application patterns, device fingerprints, and user behavior can identify anomalies suggesting synthetic fraud. These systems detect suspicious patterns like multiple applications from similar IP addresses or devices.

- Document Verification Technology: Optical character recognition (OCR) and artificial intelligence-powered document authentication detect forged or manipulated identification documents commonly used to support synthetic identities.

- Consortium Data Sharing: Participating in industry fraud-sharing networks allows institutions to identify synthetic identities flagged by other organizations, addressing the cross-institutional blind spot problem.

- Enhanced Due Diligence: Implementing stricter verification for high-risk applications, such as those with thin credit files or recent address changes, helps catch synthetic identities during the establishment phase.

What Are the Financial Implications of Synthetic Identity Fraud?

The economic impact of synthetic identity fraud extends far beyond the immediate, direct financial losses incurred by banks, credit card companies, and other lending institutions. These initial losses, which can total billions of dollars annually, represent only the tip of the iceberg. The broader consequences include:

Direct Financial Losses

Financial institutions face charge-offs when synthetic identities rack up debt and then disappear without paying. These losses have grown dramatically from $6 billion in 2016 to an estimated $20 billion by 2020, with projections reaching $23 billion by 2030.

Operational Costs

Investigating suspected synthetic fraud, managing false positives, and implementing prevention technologies require substantial investment in personnel, systems, and processes.

Regulatory Consequences

Failing to adequately prevent synthetic identity fraud can result in regulatory penalties, consent orders, and reputational damage that affects customer acquisition and retention.

Market Confidence

Widespread synthetic fraud undermines trust in digital financial services and identity verification systems, potentially slowing innovation and digital transformation initiatives.